Summary: Yes, there’s a connection between the immune system and mental health. A new study shows causal associations between immune-related proteins and seven common conditions described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (DSM-5).

Key Points:

- The study used data from the UK Biobank to identify genes related to immune dysfunction that may affect mental health.

- Researchers propose promising targets for the development of new psychiatric medications.

- Results add further support to the idea that mental health involves the body and the brain, rather than the brain only.

- Conditions associated with the immune system included mental health disorders, developmental disorders, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Body, Brain, and Mental Health

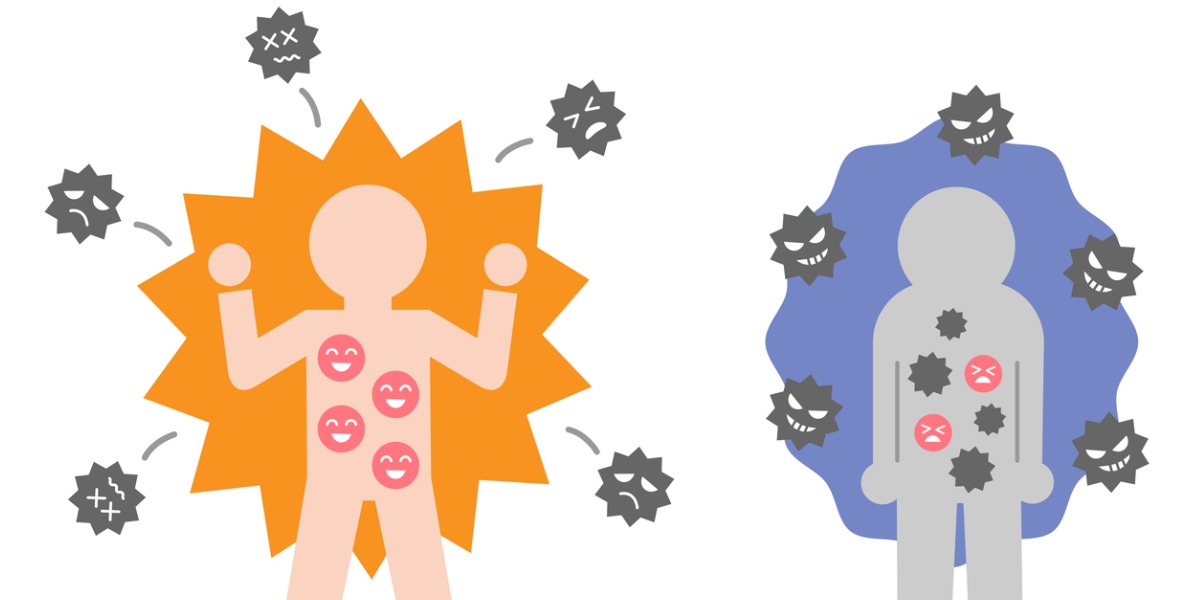

When people question the connection between the body, the brain and emotions, one thing they forget is that we experience the mind-body-emotion connection every day.

We get hungry, we get cranky. Therefore, our body affects emotions. We see something scary, get scared, and get a bad feeling in the pit of our stomach. Therefore, emotions affect the body. We think of something we look forward to, and we get jittery with anticipation. And therefore, we can see how thoughts affect the body.

When we think about it that way, it can help us understand that things not typically associated with mental health – such as proteins in the body with a specific function in our immune system – may actually have connections to mental health. Granted, this is a loose, imperfect analogy designed to help us understand this important fact: the body, brain, and emotions are connected in simple and direct ways.

Researching the Connection Between the Immune System and Mental Health

The new study “Immunological Drivers and Potential Novel Drug Targets for Major Psychiatric, Neurodevelopmental, and Neurodegenerative Conditions” looks for body-mind connections that are far less obvious than those between being hungry and being cranky, for instance, such as the connection between genes associated with immune dysfunction and common mental health disorders.

Here’s the rationale behind the study:

“Immune dysfunction is implicated in the etiology of psychiatric, neurodevelopmental, and neurodegenerative conditions, but the issue of causality remains unclear impeding attempts to develop new interventions.”

Researchers are on an ongoing mission to develop new psychiatric medication. Evidence shows that roughly 1/3rd of people with schizophrenia or depression don’t experience satisfactory results with current, first-line psychiatric medications. The majority of those medications, such as SSRIs and SNRIs, only target a subset of neurotransmitters in the human brain.

This new study looks in a different place: immune-associated proteins and how they may impact psychiatric disorders. To identify any possible connection between the immune system and mental health, the researchers analyzed something everyone has in common: our genes, or more specifically, specific parts of our DNA, called loci, which produce protein associated with our immune system.

Using a genome-wide association study (GWAS), a study design in which researchers have access to millions of patient records that make up a complete map of the human genome, the research team analyzed records from close to 800,000 genetic profiles, including patients with developmental, mental health, and cognitive disorders.

How Can a GWAS Help Us Understand the Connection Between the Immune System and Mental Health?

Here’s a definition of a GWAS, which explains why this study, and its results, holds particular salience for mental health researchers:

“A genome-wide association study (abbreviated GWAS) is a research approach used to identify genomic variants that are statistically associated with a risk for a disease or a particular trait. Once such genomic variants are identified, they are typically used to search for nearby variants that contribute directly to the disease or trait.”

To explore the connection between the immune system and mental health, the team accessed records for the following number of patients with the following disorders:

- Autism spectrum disorder (ASD): 18,381

- Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): 38,691

- Anxiety (GAD): 7016

- Depression (MDD): 460,773

- Bipolar disorder (BD I&II): 82,380

- Schizophrenia (SCZ):76,755

- Alzheimer’s disease: 111,798

To identify any potential causal relationship between the immune system and mental health, researchers used a statistical tool called two-sample mendelian randomization (MR), in which a second set of data reveals any potentially confounding factors, which allows for reliable estimates of causality between two variables – in this case, between immune dysfunction related to genetic loci and mental health disorder.

In this study, the research team looked at the relationship of 735 immune response related proteins measurable in human blood. Of these 735 immune proteins, they found 29 proteins in the immune system connected to mental health. The mental health disorders associated with immune system proteins include:

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Bipolar disorder

- Schizophrenia

- Anxiety (GAD)

- Alzheimer’s disease

- Autism spectrum disorders

- Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

Among the 29 proteins in the immune system connected to mental health, most associations revolved around immune-related inflammation in the brain and body. The research team identified 20 that may be affected by preexisting medications designed for other medical conditions. They concluded that these proteins – as well as the remaining nine – are ideal candidate targets for new psychiatric/mental health medications, in addition to the possibility of repurposing existing

Mind, Body, the Immune System, and Mental Health

Here’s how Golam Khandaker, Professor of Psychiatry and Immunology and MRC Investigator at the University of Bristol Medical School describes the results of the study:

“Our study demonstrates that inflammation in the brain and the body might influence the risk of mental health conditions. The findings challenge the centuries-old Cartesian dichotomy between the body and the mind. They suggest that we should consider depression and schizophrenia as conditions affecting the whole person.”

We agree. Mental health and treatment for mental health disorders requires a comprehensive, whole person, mind-body approach. The fact that a significant number of patients don’t respond well to first-line treatments for conditions like depression or schizophrenia means the discovery of new medications that work in an entirely different way could improve lives for millions.

We’ll keep an eye on the research into this topic. We’ll report back here as soon as we have new information about how we can help our patients with complex, treatment-resistant mental health disorders.

Gianna Melendez

Gianna Melendez Jodie Dahl, CpHT

Jodie Dahl, CpHT